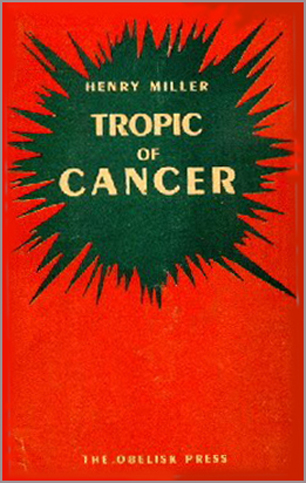

My view of him was also prejudiced by my reading, over 20 years ago now, of Kate Millett’s feminist polemic Sexual Politics, in which she does a hatchet job on Tropic of Cancer, condemning Miller for his sexual violence, misogyny, homophobia and anti-Semitism. One of my curiosities in reading Miller was to discover if his work had any literary merit beyond its status as a Famous Banned Novel, or anything to offer a contemporary, post-#MeToo readership. “It is a cesspool, an open sewer, a pit of putrefaction, a slimy gathering of all that is rotten in the debris of human depravity.” Despite these objections, the Court agreed by a 5:4 margin to reverse a ban on the American publication of Tropic of Cancer, sealing Miller’s reputation as a literary bad boy, and a vanguard in the long fight against censorship laws. “Not a book”, grumbled Justice Michael Musmanno in a 1964 US Supreme Court trial. Why it’s a classic: “ This is not a novel“, Miller proclaims in his opening pages – and for many years, history agreed with him. Miller’s narrative flows loosely between episodes of sex, drunkenness and petty crime, stream-of-consciousness reflections on mortality, disease, the nature of being and the decline of civilisation, and stirringly vivid descriptions of grimy bohemian Paris. What it’s about: A freewheeling, cheerfully pornographic account of American writer Henry Miller’s life among the down-and-outers of 1930s Paris, recounting a nomadic existence of grinding poverty and hunger, a larger-than-life supporting cast of barflies, hustlers, prostitutes and no-hopers, and graphic accounts of loveless, often abusive sex with women.

In which I review Tropic of Cancer, Henry Miller’s 1934 novel about life in the sex-and-boozed drenched squalor of 1930s Paris.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)